DOWN MEMORY LANE

A HISTORY OF OUR FAMILY AS RECALLED BY THOMAS W. REED (Formerly Weiszbluth Gyozo Tamas, Thomas Weiszbluth and Thomas Weissbluth)

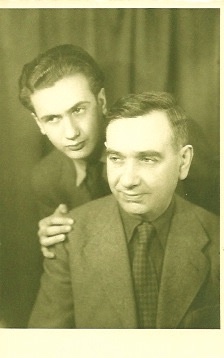

Its 2006 and I am 77 years old, married for 53 years to my wonderful wife with whom I am very much in love, former Lora Alpert Gold, and I want to write this book for my living descendents and generations to come. Please note that the hero of our history is undisputedly my father, Eugene Weissbluth, formerly Weiszbluth Jakab (generally known as Weiszbluth Jeno), who not only saved my life against all odds, but also did everything humanly possible to give me an opportunity for a higher education and through me re-established our decimated family. The details of these introductory statements will reveal themselves in the pages of this book.

FAMILY BACKGROUND

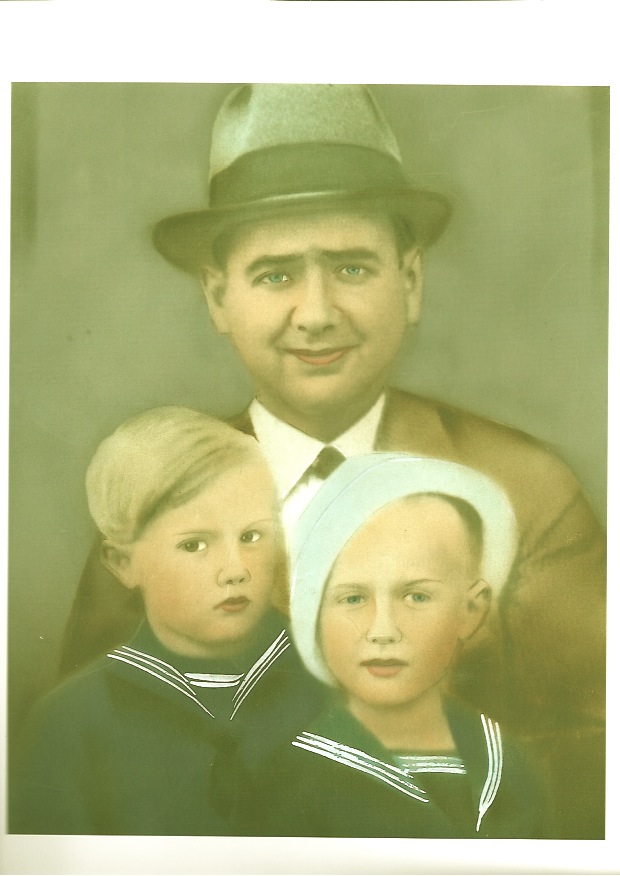

My immediate family in 1944, on the eve of the Holocaust, consisted of my father, Eugene Weissbluth (aka. Weiszbluth Jakab in Hungary, with the Hebrew name “Jankev”), my mother Rozsa (maiden name Rosenblum, her Hebrew name was “Rachel”, I was Weiszbluth Gyozo Tamas, nicknamed “Tomi”, with the Hebrew name of “Avrohom”. My brothers were Gyorgy Tivadar (“Gyuri” and with the Hebrew name of “Menachem Mendel”), Oscar Ivan (“Oszi” and with the Hebrew name of “Arye Leib”) and Alfred Denes (Fredi and his Hebrew name was “Eliezer Zvi “). My little sister was Judith (Juditka and her Hebrew name was “Keile” and her nick name “Mucus”). Juditka was a blue and blond little girl. Younger brother Oszi, Juditka and I had our father’s blue eyes. I was the oldest of the children and in 1944, at the start of our tragedy; I was only 12 years old. My siblings were aged in descending order, 10, 8, 6 and 4 years old. My mother was a pretty lady, talented amateur painter, pianist, housewife and courageous woman. My father was the principal and a teacher of the Jewish elementary and middle school (combined duration eight years) in our town of residence, Mezocsat, Hungary. He also taught German to private students and part of the year, he taught in the agricultural school. My father was always deeply involved in helping individuals with problems in the Jewish community and frequently represented parties in front of the rabbi’s court. On a number of occasions in the ”old days” he was “second” for dueling Christian friends.

My grandfather on my father’s side was Josef Israel Narcisenfeld (Yechiel ben Simon) married to Golda bas Avrohom. They had a set of twins that died at birth and their oldest was Lajos (Louis) Kiss followed by my father. Uncle Lajos had married twice and had a son Dezso (David) from his first wife. The reason for the differences in last name was related to my grandparent’s citizenship problems that had to be covered up by bribing a government official to avoid deportation and subsequent murder of those deported. This was the fate of 17,000 Jews deported from Hungary in 1941. My father took out a loan to obtain false papers that worked. My mother has discovered the loan after my father was drafted and no payments were made on the loan. My father would not talk to me about it all, except that my grandfather was born in Munkacs that is in now Rumania. A “man”, a jerk, in our community, to belittle us, told me that we were originally from Poland. Being from Poland was considered shameful. Regarding my Uncle Louis, he had proposed marriage to the girl who became his first wife and David’s mother. Actually he wanted to break the engagement, but my grandparents would not permit it. They told him that he could not shame a decent girl by such action. Later he divorced her and remarried.

My grandparents on my mother’s side were Armin and Tini Rosenbloom and they had two sons and five daughters. All of my life, I only remember meeting my maternal grandfather once and my maternal grandmother twice. The first occasion was when my father was discharged from the Hungarian Army and picked up Gyuri and me from the home of my Mother’s oldest sister, Blanca, in Rohod. The second time I saw my Grandmother was when she came to visit us in Mezocsat. Upon arrival she gave each of us a “pengo”, which looked like a silver dollar). A few days later she “borrowed” it back for good. To our amazement, she found and visited a woman who was a fortune teller and she enjoyed making an drinking “tea” from our poppy seed plants-the part that held the seeds we that we had ground for our Saturday morning poppy seed cakes. Apparently she suffered from high blood pressure that those days could not be treated. After a few days she started saying she was going to die and we had to send her home to Sarospotak. The Rosenblum home was located on a main street. I remember the grand piano and numerous unfinished oil paintings left by my mother and her sister, Etus. While in Sarospotak, we met briefly with with my Uncle Jeno, Aunt Dora Rosenblum, amd their son, Gabe (father of Karen “Rosie” Rosenblum Stafford). We visited the “Rosenblum and Son” lumberyard, which occupied all of the land across from the railroad station. We also went to visit Aunt Margit at Satorajaujhel (she was the youngest of the Rosenblum girls) and her two little sons. She was married to a Silberman, who at the time was serving as a laborer in the Hungarian Army. She had to run their hardware store located on the street leading to the railroad.

She did not approve of any of her son in laws, but my father “bribed” her with books since she was a voracious reader.

As you can imagine, managing five healthy kids was not easy for my parents, especially me, who was always up to something. I liked climbing up on the roof, dismantled my mother’s only clock, taking down the electrical wire between our two buildings, did not want to pray, tried to skip attending the Temple, studying the Bible etc. Thus, I was a difficult child who had to be spanked and exiled to the corner frequently. Compared to me, my siblings were angels. I loved to read and play with other kids of my age. I think that I wanted a more modern environment than was available to me. Might as well remember that you are my descendants!

My friend Joe Gajducsek and I snuck behind his Aunt’s outhouse to smoke a “levant” cigarette that resulted in lots of coughing and no pleasure. One Friday, Joe and I went to the ritual bath (the “Mikveh”) early in the day and found a long wooden washtub floating in the water. Lo and behold, we had boat! We jumped in and happily paddled around until Mr. Daskal, who also took care of the Mikveh, happened by and was shocked to see us paddling around in the tub that was used to wash the community’s dead prior to burial.

One warm day, while attending Torah classes, my teacher, Mr. Friedman nodded off to sleep while we took turns reading out loud. Being the unruly child that was, I melted red sealing wax onto his beard, thus gluing him to the table. I obtained the wax from my friend Shaje Krauss, whose father used it in his wine business to seal bottles of kosher wine. Upon waking, Mr. Friedman tried to sit up but his beard would not move. His eyes widened when he realized his predicament. To make long story short, most of his beard had to be cut off and I was spanked very hard, Actually, I am not proud of what I did but I was a very bored and mischievous boy.

We had an outhouse at our home in Mezocsat. At night, the house was locked up and we used night pots, which we routinely emptied int he morning. One night, foursome reason, rather than use the night pot, I peed in the maid’s shoe. I only did it once as I received a hard spanking for my actions.

The Jewish community was established in about 1828 as a very strict Orthodox congregation. A Temple was built that eventually burnt down, only to be replaced by an impressive two story building. Who we visited it was in a state of semi-ruin, because of a lack of maintenance since 1944. The town of Mezocsat “owned” the building and had rented it out as a warehouse and the tenant destroyed the interior and failed to maintain the windows, stucco exterior and roof. Since that time, The Temple has been restored by the town and is now used as a community center. It was a well established community with about a dozen non-religious families who also had to pay the community “religion tax”. Except for a Christian owned corporation called “Hangya” (ant) that owned several stores, established to compete with Jewish owned businesses, all stores and enterprises were owned by Jews. Grocery and hardware stores was Glattstein (we shopped there almost exclusively), Friedmann, Saros, Breier, Beck, Droth and others. Clothing material by the yard (not clothing) stores were owned by Carl Roth, who also sold shoes, Friedlander (who was also the President of the community and died a few days prior to our being deported), Saubermann and others. Sirmer and Heinfeld each owned a lumberyard. Mr. Krausz (his son, Siu, was a friend of mine) made and sold wine. Mr. Mehrer sold and repaired radios. Mr. Ferenczi sold and repaired large clocks and we actually stayed in one small room in his house during our few weeks of stay in the ghetto in Mezocsat. Mr. Stiller was a shoe maker, and Messers Szaz and Mehrer made and delivered soda water. Mr. Loebel was one of two pharmacists in town (later the Christian license holder, Mr. Orosz took the business from him). Farm owners included Szekulsz, Resovszki, Borgida, Winkler and others. Attorneys were Dr. Furesz, Dr. Goecze and Dr. Bergmann (he survived the Holocaust and become a Judge, first in Mezocsat and later to a higher court located in Miskolc. His son Tibi was a friend of mine. The only dentist in Mezocsat was Dr. Kardos, who was also physician. The other physician was Dr. Abonyi and the veterinarian was Dr. Winkler. Mr. Kolozs owned the only mill and his wife survived. Mr. Engel owned the only bank (his son, Laci, married a Christian woman and he and his children escaped deportation. Laci’s sister survived the concentration camp but as a result of her experiences, had mental problems. There were several grain dealers town as well. Our Rabbi was Fabian Altman, whose son “Schema” was a classmate of mine. The had cantor and also one of the two ritual slaughterers (the “schochet”) was Mr. Cohen and the second was Mr. Daskal (He also took care of the ritual bath or “Mikveh”. His son, Mayer, was my Hebrew teacher starting when I was three years old and my long blond hair was cut off. Mayer ended up in Cleveland, Ohio and become the owner of several large nursing homes. Shagra Neumann, a wonderful individual (who also survived the Holocaust and ended up in Israel) eventually replaced Mayer. Mr. Friedman and later his son in law, Mr. Berkowitz, taught religion (reading the Torah) in Hungarian language at my father’s school. It was interesting that the Orthodox community did everything they could to prevent Zionist youth from departing to Israel while the escape routes were still open. The generally strong anti-Zionist views of the Orhodox views was well known.

As a child, I had a nice life. The first thing I remember is that I was in part of our yard that was covered ingress and the son of the only blacksmith in Mezocsat, wearing a jacket with red vertical, blue and white colored stripes lifted me on his back. My parents told me that I truly scared them when I, as a very small boy, took my brother George out of his crib and carried him out the tiled patio although I have no memory of having done so. I was enrolled in a non-denominational Kinder Garden but I did not adjust well to being away from home and as a result, my parents removed me from the situation. When I started school, we mostly played with Jewish kids and our Christian neighbors. Our most fun was playing “hide and seek” in our peasant neighbor’s yard with its large gardens, straw stacks, hay stacks and many auxiliary buildings. In the summer we very much enjoyed our metal bath tub in our yard, heated by the sun. We bathed naked along without usual guest, Anni Hoffman, who survived the Holocaust along with Zoka Landsman and a friend of mine, Joe Gajducsek. My parents loved to read and they had a 2000 volume library that was acquired with part of my mother’s dowery. There was a night light that was in use every night except Fridays. I also loved to read laying on the floor. I even had my own library, having read the Hungarian classics by age twelve in Hungary.

The Zionist youth was to wait until the coming on the Messiah before going to Israel. I even witnessed fistfights in my own community of Mezocsat in the Temple and the Temple yard to prevent he religious Zionist “Augudas Yisroel” youth organization from having a Torah to use in their Orthodox religious services.

While on vacation in Rohod visiting the Gruenwald family, my Aunt Blanca enrolled me in “cheder” to study Torah each day. This consisted of reading the weekly Torah portion in Hebrew and translating it into Yiddish. Since I did not speak Hebrew or Yiddish, did not like the Melamed or have any interest in studying Torah, my hand had many painful meetings with the Melamed’s (teacher) wooden stick. The cheder was held in a building that had previously been a tavern with a space below the floor used to keep the alcohol reasonably cool. One day I convinced my fellow students to play hide and seek anti lthe Melamed got there. As I expected, they all hid in the below the floor cavity and I locked the trap door. When the Melamed arrived I met him outside and told him that since I was the only one in attendance, we should go home. By then the other kids realized that I had locked them in the and started banging on the trap door. The Melamed heard the knocking and let them out-I knew I was going to get a whipping so I jumped on the table and out the open window and ran through the unfenced gardens towards “home” with the Melamed chasing me. Aunt Blanca had mercy on me and I no longer had to go to cheder.

Just before my father was discharged from the Hungarian Army, my mother took Gyuri and me to the home of her older sister, Blanca Gruenwald, in Rohod, for a vacation. We had to change trains in Miskolc and then in Nyireghaza to go to the Baja-Rohod station, Rohod, a small village without electricity, was the home of the Gruenwald side of the family. The train stopped at the Village of Vaja and a number of miles from Rohod. During our required layover in Nyiregyhaza we visited a cousin in of my mother and ate dinner at their kosher delicatessen. Upon arrival in the dark at the Baja-Rohod station we waited in vain for at least an hour for the buggy to come for us. After that we walked into Vaja and knocked on the window of a peasant’s house and asked for a bed to sleep in. They vacated one of their already slept in beds and all three of us slept in it. The next day word went out to the Gruenwald family as to what happened and a buggy was sent for us but it arrived so late that we were not able to depart until the following day. We had wonderful vacation. My cousin Hersu (Herman) was very interested into young ladies who were visiting at the same time so we saw little of him. We did however get to spend lots of time with Potyi and Alice, who were both wonderful. Uncle Toni and Aunt Blanca could not have treated us any more nicely either. Uncle Toni took us to his farm where he grew wheat and tobacco. The tobacco was dried in large ventilated barns. The workers and their families lived on the farm. The workers smoked dried tobacco cut with their pocket knifes and wrapped in newspaper to make cigarettes. When it was time to deliver the wheat to the railroad station in Vaja, I rode on the last wagon to make sure the farm hands did not drop any bags over the side if the wagons and into the ditches to be picked up later.

The Hungarian Army was destroyed by Russia at Stalingrad and the remnants retreated to Hungary. Upon the return to Hungary via a long march, they were discharged. My father immediately contacted the government education officials to collect his back pay. The officials told the community that the payments their responsibility and that if they did not pay up, the government would seize the “gabela” (the money collected for the kosher killing of animals) by both of the kosher butchers (Mr. Cohen and Mr. Daskal).

Then my father took Gyuri and me home via a visit to our Rosenblum grandparents and my Uncle Jeno and family (Aunt Dora and cousin Gabe) in Sarospotak. We then visited Aunt Margit (Margaret Silberman). Aunt Margit’s husband was still away serving as a forced laborer. At Sarospotak I met the above persons for the very first time except my grandmother who visited us in Mezocsat. This was also the last time I oversaw them again. To be with our father was the most happy we could be after his absence.

My Mother has a live in maid after each of her pregnancies and at least after Freddy was born, my cousin Edith came to help us. My Mothers like was hard in that with the exception of short periods of time, she had to do EVERYTHING for the family, including cooking, washing clothes and children, mending socks, planting and harvesting the garden, feeding the poultry, planting flowers and watering the flowers and vegetables. The children helped whenever and however they could-they watered the plants, got milk from the neighbor (Mrs. Torok), made butter, got water from the well, took the poultry to the kosher butcher, took cholent to and from the baker, ran errands, etc. To fertilize our garden, we had our neighbors spread raw manure mixed with straw and we spaded that into the ground. After planting, we hoed the ground around the growing plants although my father and the very young children were exempted from this work. Mother knew exactly what to do and when. The plantings generally consisted of potatoes, corn and many different vegetables. Yearly rotation between the potatoes and the corn planted areas was performed. When the potatoes started growing, we dug under the plants and took some of the young potatoes for cooking. We had both red and black berries, mulberry (buske) and currant (ribizly) bushes along the edges of the garden. The neighbor had “ever” trees and their fruits were always available to us. In 1942 we we had about a dozen dwarf fruit trees planted in the garden. They had some fruit on them by 1944 but according to Jewish law, we could not eat them until they were three years old and by then we were deported to Auschwitz. When I visited Mezocsat in the late 1990’s with my wife, son, daughter in law and grandson Alex, they were already gone. However, I did find some “buske” bushes and enjoyed their fruit very much. Our water came from a well located outside our winter kitchen. We used a bucket lowered with a solid lead counter weight balanced by another rod that went through ha “v” shaped tree with weights at the dar end of it. The water always had things floating in ti that we spilled out onto the ground. We never washed our fruit and drunk the well water without any ill effects.

The menus changed with the season and depended on what grew in the garden, what was available in the outdoor market (piac). and what the extensive results of my Mothers canning. Our weekday menu focused on my Mothers baked rye bread for toast, the butter made, jams/lekvar and chicory coffee with sugar and milk for breakfast. Our main meal was lunch and it was based on a hearty vegetable soup along with bread and jam/lekvar. Dinners were similar to breakfast-scrambled eggs fresh from our chickens, were frequently added to either lunch or dinner. We always had bread, jam/lekvar and goose liver available to us. The house had a summer and a winter kitchen. Fresh fruits, vegetables along with melons were all available to us, depending on the season.

Friday night meals were special. They consisted of Challah, chopped chicken liver, chicken soup with chicken feet along with unlaid eggs (yellow balls), stuffed chicken and nickel. Saturday morning we had delicious cakes with an array of fillings, including ground poppy seed dmixedwith powdered sugar and coffee. The lunch was sometimes coolant with dumplings-they were varied and more extensive than I am describing here but I cannot recall the details now.

Our clothing was always appropriate for our age and style in fashion. My father and mother were eloquent dressers-handmade by a tailor or dresser as applicable. We always damaged the toes of our shoes by playing soccer. Wearing overshoes was necessary when it rained hard or snowed since with the exception of the Main Street, none of the roads were paved. I slept with my brother Gyuri on a “divan” (a day bed) and while the bedroom oven was seldom used.

The World War II deportations resulted in almost 500 deaths in my community by gassing and other inhuman ways, including starvation, being worked to death, being beaten to death, being shot, exposure to the weather, forced marches, torture, so-called “medical experiments” and frequently, children and old people were burned alive at Auschwitz. The very few people from Mezocsat who survived the camps returned only temporarily to Mezocsat as I was only aware of four people who stayed there. My wonderful cousin Edith went to Mezocsat to gather what might have been left of our belongings. There was nothing left except what my Mother left with Mrs. Farkas Oliver, a wonderful lady and an ex-neighbor from when my parents lived in Mr. Barany’s house. She returned to Edith my Mother’s diamond engagement ring (a one carat diamond), her silver purse and my father’s gold watch chain. My Father sold the watch chain, gave the diamond ring to my step mother Trudy who unfortunately left it out when a burglar broke into our apartment on Eddy Road in Cleveland Ohio and stole it and I gave my daughter Judy my Mother’s silver purse for use by her daughter, Saree. The fact is that the deportation of the Jews of Mezocsat destroyed the Jewish community of Mezocsat and only the ruined temple and cemetery remain. The only Jew left left when we visited as a family was these of a survivor who is married to a Christian, No one that I know of in the Christian community stood up for us. Therefore, without exception, seeing or even thinking of Mezocsat and its people make me sick. They only thing they did not do was to desecrate our cemetery, probably because there is no profit in it. One Jewish survivor, upon returning to the town without his family, killed himself. What was there to go back to and live among people who in general hated is and happily plundered our hard earned belongings?

Although there was always antisemitism in our region but it only got worse as the barraged. My brother and I were threatened by a young man with a knife. When my Mother complained to the Police she was told that there was nothing they could do. In March of 1944, Germany occupied Hungary, in part out of fear that Hungary was conducting secret talks with the Americans. In April of 1944, the order to remove 437,000 Jews from from provincial towns villages and cities (other than Budapest) was issued by Adolph Eichmann. As bad as the Nazi’s were, part of the horror was that the deportation orders were faithfully carried out by Hungarian officials, led by the Hungarian police. Without the eager cooperation of the Hungarians this and the deportation to Auschwitz would not have happened. Amazingly, there were less than one hundred Germans assigned the task. The Hungarian agent government carried out these tasks eagerly, in many cases, with cruelty and they handed over the entrained Jews to the Germans for destruction in Auschwitz. From their homes, the Jews were forced into local ghettos and then assembly areas and then to Auschwitz. There w s essentially no protest against these actions any the Hungarian people. The Christian Churches did save some Jews who had Christian spouses. We were forced out of our homes in Mezocsat and made to report to an area of town. We were forced to walk to the railroad station where we were roughly placed in cattle cars which were very crowed and unsanitary. People begged the Hungarians for water as we sat in the cattle cars. We were taken from Mezocsat to a brickyard in the town of Diosgy, near Miskolc. We spent several weeks in the brickyard which served as a regional gathering place for deported Jews. There was no privacy and no separation of families. All of us used an open trench as the bathroom.

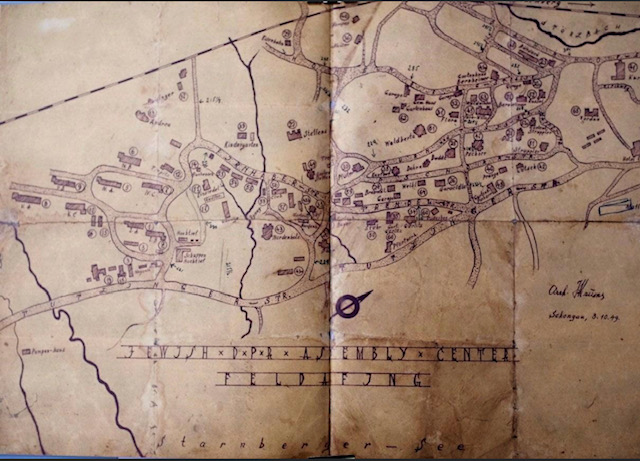

After the war, some Jews wanted to return to their homes. Unfortunately, there were no laws passed regarding the return of Jewish property and there were programs in some cities and villages where returning Jews were killed. These programs occurred in Kunmadaras, Miskolc and other communities. My father wanted to return to Mezocsat and rebuild our lives and I wanted to emigrate to the United States. My Father finally agreed and we started the paperwork process. In order to emigrate, not only did we have to have the necessary paperwork prepared and background checks performed, we had to wait until we fit within the quota of Jews allowed in and we had to have a sponsor who would guaranty that we would not become a financial burden on the government. My father had distant relative who was an accountant in Cleveland Ohio and he was part of a small congregation in search of a Rabbi. As an aside, my father came from a long line of Rabbis-One of his ancestors, a Rabbi, was the chief judge in the Court of the “wonder rabbi or Satorajaujhel and is buried in a local cemetery. While being a Judge, a woman came before the Court claiming that a ghost had impregnated her. Superstition about ghost (“shedem”) who could impersonate people and impregnate women were believe in by a segment of Jewish society. That same ancestor’s son visited the city regularly on the anniversary of his father’s death and to say Kaddish at at his grave. He usually stayed overnight in the City and left the next day. However, on one occasion, his father appeared to him and told him that he “was very lonely”. The son got scared and left the city, never again spending the night there. In 1439 we were finally told that we could leave Germany and go to our new home-The United States of America. Finally, we were on the U.S. General Ballau headed to the US. We went through Ellis Island and were greeted by Gertrude Guttman (who became my Father’s second wife). We spent only a few weeks in New York before departing for Cleveland. I was fortunate because Gertrude had helped me learn English while we were in Feldafing so I could speak some of the language. My father went to work as the Rabbi and we worked factory jobs to help make ends meet. We rented a room where we shared a bed and had kitchen privileges. We wore blue jeans when the only others who did so were farmers and we were hard pressed to even afford toothpaste. My father knew that I needed to continue my interrupted education. He obtained or perhaps prepared forged documents stating that I had graduated from high school. I was admitted to college, barely able to speak English, and studied engineering. I was asked to join a fraternity but declined to do so as I needed to focus on my studies. My father sold part of his stamp collection to help me with my college fees and through his hard work and sacrifice, and then later the GI Bill, I was able to not only finish college but later attend law school at night while working 48 hours a week as an Engineer at what was then North American Aviation, which later became Rockwell International and ultimately, Boeing.

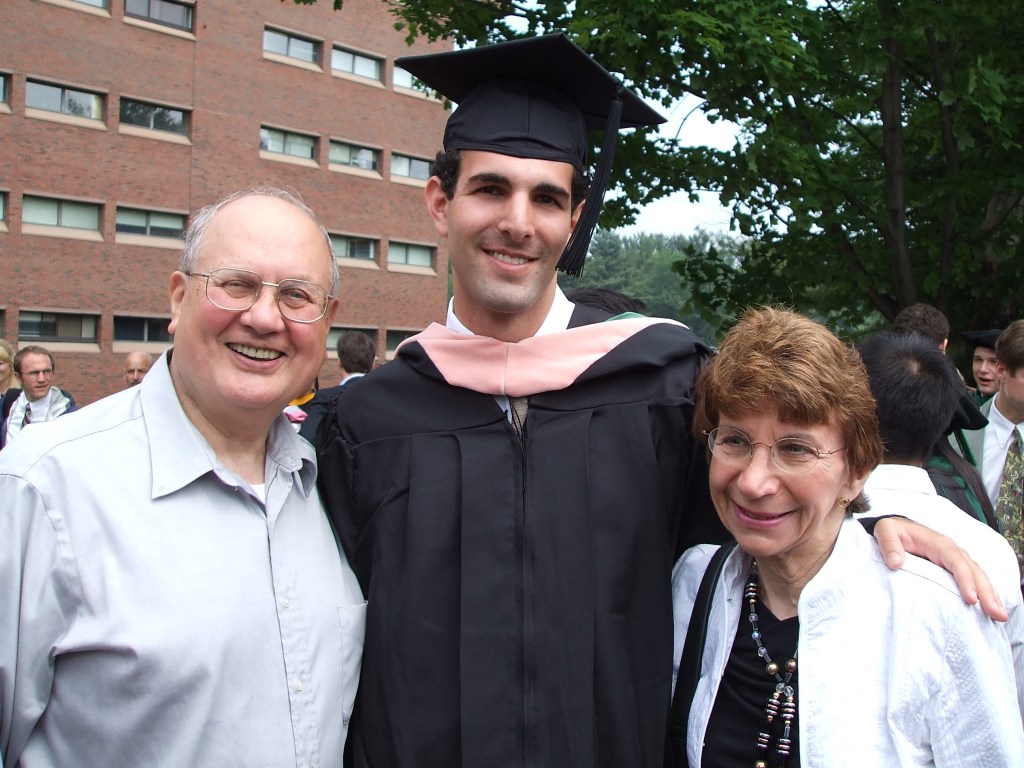

While pledging a fraternity during September of 1950, I went on a triple date and met my future wife, Lora. She was the date of a fellow wo later become one of my best friends. While on leave from the Army, Tom met Lora again at Hillel and a romance bloomed immediately. After I left the Army, Lora and I got engaged and on September __, 1955, (Labor Day), against all sensible advice, we got married. Lora quit her studies after finishing her junior year as a biology major at Western Reserve and became the Biology Department’s Librarian. By the time I received my B.S. in Electrical Engineering, I had received 16 job offers and accepted a position with North American Aviation, Columbus Division. We moved to Columbus, Ohio and Lora changed her major to American History. Our first child, Mike, was born August 8, 1956 and I started law school at Franklin University (now Capital University). Lora received her B.A. and continued on for a B.S. My LLB was replaced by a JD. When I graduated from college I was fortunate enough to marry my college sweetheart-my “Hillel girl”. My father asked us to come over and receive a special blessing from his Rabbi the week before our marriage. It turned out that my Orthodox father did not believe that we would really be married in the eyes of God if we were married by a Reform Rabbi so he had his Orthodox Rabbi marry us in a Jewish ceremony without our knowledge.

One of my father’s primary goals in life was to recreate our decimated family and I was thrilled that my father lived long enough see our family well on the road to recovery. He loved and sacrificed for his grandchildren, buying each an insurance policy that would pay off when they were teenagers. Every visit with him meant a visit the story to buy grocery bags of candy and of course, sugar free gum for the grandkids and Brach’s chocolate covered cherries for my wife. He was also very much in love with his great grandchildren.

HUNGARY

Jews lived in Hungary for 1900 years, from the time of the Roman Province Pannonia. Within this province the Jews lived in a number of places in what is now known as Hungary. These places include Aquincum (Budapest), Solva (Esztergom), Sopianec (Pecs). This fact is clearly demonstrated by the remains of old synagogues, ritual baths, head stones and other items displayed in museums, such as the Vari Museum in Budapest. In the late 800 AD, seven Asian pagan tribes from Asia united and took over the area that is basically known as Hungary. The tribes were excellent mounted fighters and mainly lived from plundering the Western European Christian countries, including France, Italy and Germany. In 998 AD the tribes were severely defeated by a Germanic King named Otto, near Augsburg, Germany, as they were trying to cross the Danube with their plunder. Subsequently, the tribes withdrew to the general territory now known as Hungary and elected a tribal leader, Stefan, as their king, to seek peace with the Western European countries. King Stefan, who later was known as Saint Steven (aka. St. Stephan), sent a delegation to the powerful Pope of the Holly Roman Empire requesting permission to settle down in peace on their occupied territory in exchange for converting to Christianity. The Pope agreed and sent Steven a crown and missionaries to Christianize the tribes. Steven ordained that no person shall be “forced” to covert, but those who do not will be buried alive. After a number of missionaries were slain, including Saint Gelert after whom a hill is named in Budapest. The tribes became Christian and their area became known as Hungary. Subsequently Steven was ordained Saint by the pope. His supposed right hand is a religious relic that is paraded on Saint Steven’s day in Budapest.

Noteworthy that Hungary had two categories of police, namely one for the cities called ”rendor” (order guard) police and one for the rest of the country called “csendor” (quietness guard) police. Mezocsat had “csendors” who were primarily trained to deal with peasants and they were rough individuals. The two categories wore different uniform and carried different weapons. After WWII because of the csendors shameful dealing with the deportation of Jews and their associated crimes their organization was merged into that of rendors.

JEWISH LIFE IN HUNGARY

In the later part of the 9th century, the Jews in the Asian said Roman provinces along with other natives, came under the conquering barbarian tribes, led by a leading chieftain named Arpad. The Jewish community, being relatively very well educated and useful to the barbarians, has greatly expanded in the 11th century through immigration from Germany, Bohemia and Moravia. In 1092, restrictions were placed on the Jewish community, the Christian clergyforbid intermarriage, owning slaves and working on Sundays and Christian holidays. At the end of the century King Kalman placed special taxes on the Jewish community in payment for protection. However, by the end of the 12th century Jews held leadership positions in the country’s economic institutions. Subsequently, in 1251, King Bela gave the Jews legal rights and welcomed Jewish immigration. Unfortunately, the influence of the Christian church greatly expanded under King Louise (1342-1382) and in 1349 the Jews were expelled from Hungary for being accused of causing the Black Death. Than, starting in 1364 Jews were permitted to return.

The situation for the Jewish community has improved under Matthias Corvinus (1458) also known as King Matyas. Once again the economic and political situation deteriorated, resulting in of 16 Jews being burned at stake. Other riots also occurred. King Ladislas (Laszlo) cancelled all debts owned to Jews. During the subsequent reign of Louis II (1516-1526) the anti-Semitic feeling grew even stronger. Following the Ottoman conquest of a large part of Hungary in 1526 many Jews joined the Turks to migrate into the Ottoman Empire. This led to the dispersion of Hungarian Jews into the Balkan region. In 1541 central Hungary became an official part of the Moslem Ottoman Empire and Jews were once again allowed to practice their religion and participate in commerce.

In the late 17th century the Hapsburgs “liberated” Hungary, kept it part of their conquered territories and anti-Semitism resulted in expulsion of Jews from the cities. Despite of all this immigration of Jews grew from Poland and Moravia where the situation there for the Jews must have been worse. By 1735 about 11,600 Jews lived in Hungary. However, situation for the Hungarian Jews became even worse under the reign of Maria Theresa (1740-1780) the Jews were forced to pay “toleration” taxes and faced other persecutions. Regardless of all these, by 1887 about 81,000 Jews lived in Hungary. Subsequently, under Joseph II the harsh conditions were finally reduced and Jews were granted civil rights in 1830 and also Jews were permitted to settle in a selected number larger towns in 1840.

In 1849 Jews participated in a failed revolution against the Hapsburgs and in retaliation again judicial and economic restriction were placed on them during the 1850’s, which were finally lifted in the 1860’s. In December 1867 Jews were granted full emancipation. Thereafter, Jews began playing a vital role in agriculture, transport, communication industries, business, finance and the arts. The Jewish population continued to increase from 340 in 1850 to 542,000 in 1869. The Jewish religion was fully recognized by the state and given the same rights as the Protestant and Catholic religions. Yet, anti-Semitism has increased in the 1870’s and 1880’s. A blood libel trial took place in Tiszaeszlar in 1892. Dessspite of all the Jewish population has increased to 910.000 by 1910 in Greater Hungary that was subdivided after WWI under the Trianon Treaty. Jews became 55 to 60 % of all Hungarian merchants. In World War I (WWI) 10,000 Jewish soldiers lost their lives in the Austrian-Hungarian Army on the Eastern Front. My uncle Louis was a first lieutenant and received a silver star for rescuing a supply train from Russian attack. He contacted malaria that has reoccurred after the war and his heart could not take the induced fever that was the accepted cure. He is buried in the Jewish Avas cemetery in Miskolc.

The strong prevailing religious trend of the Jewish communites was toward strict orthodoxy, but enlightenment came to the Hungarian cities in the form of reform movement (Haskalah). The late 19th century, 1869-1870, was marked by a religious schism. This resulted in three main divisions: Orthodox, Neolog (Reform/Conservative) and Status Quo Ante (not associated with Orthodoxy or Neology). Assimilation became wide spread and especially many young Jews began to inter marrying and conversions were relatively frequent. By 1944 there were 100,000 Christians designated as Jews under the racial laws of Hungary.

The allies at the end of World War I (WWI) dissolved the Austrian-Hungarian empire and Hungary became independent, but under the Trianon Treaty lost a very significant part of its territory and population to the neighboring states. The remaining Jews lost their importance in that their votes was no longer required to prove to the Austrians that the Hungarians were a majority in their claimed territory. Unfortunately, a communist regime gained power with many Jews active in the upper echelon of the government, headed by a Jewish man, named Bela Kun. In 1919 the brief Hungarian-Soviet Republic ended and was followed by a series riots and violence against the Jewish communities, known as the “White Terror”. More than 3,000 Jews were massacred. By 1920 the political situation stabilized and the violence abated, but the anti Jewish sentiment did not wane. A law (“Numerous Clauses”) was passed reducing Jewish access to higher education to 5%. However, some regional universities did not strictly observe said law. A Jewish community fund was established to help Jewish student to study abroad. Anti Jewish legislation continued in the 1930’s. In 1938 the “first Jewish law” was passed, restricting the number of Jews in liberal professions, administration and commerce to twenty percent. In 1939 under a “second Jewish law” the 20% was reduced to 5% and altogether 250,000 Jews lost their source of income. As a result thousands of Jews converted to Christianity. To combat the loss of work and poverty the Jewish community has established a social aid program. Over half of the Jewish population moved to the “greater Budapest area”.

Hungary joined the Axis powers in World War II and as a reward was permitted to reoccupy parts of their post WWI lost territories from Slovakia, Transylvania, Yugoslavia, and Sub-Carpathian Ruthenia. As a result of these the Hungarian Jewish population has increased to 800,000 in 1941. In addition to this there were up to 100,000 coverts including their descendents. Also in 1941, 23,000 Hungarian Jews who could not prove their citizenship were transported by the Hungarians to the German occupied part of Russia and shot by the Germans.

A “Third Jewish Law” was passed prohibiting intermarriage and changing the definition of a Jew to racial definition. Thus, the converted Jews and their descendents, estimated 50,000 to 100,00 became Jews again. Thus, the estimated number of Jews in Hungary became 850,000. A massacre of Jews took place in July 1941 when 20,000 Hungarian Jews were expelled from the Galicia region of Kamentes-Podolski to be murdered by Hungarian troops and German SS. Another massacre of 1,000 Jews took place in Hungary’s Bacska region carried out by Hungarian troops and police units in January 1942. Further, in WWII while serving in the Second Hungarian Army as laborers 50,000 Jews men died on the Eastern Front. MY FATHER, EUGENE WEISSBLUTH, WAS ALSO DRAFTED IN 1941 INTO A LABOR UNIT (AFTER A LONG FORCED MARCH WITH THE REMENANT OF THE DEFEATED 2ND HUNGARIAN ARMY) MANAGED TO GET HOME FROM RUSSIA IN 1943. Also, as described above, 23,000 Hungarian Jews who could not prove their citizenship were handed over to Germans who shot them in the occupied part of Russia. My father’s parents escaped this fate because my father purchased for them fake citizenship papers. They were later killed in Auschwitz.

In 1942, Miklos Kallas, prime minister, ordered a large segment of Jewish property to be appropriated and proposed a “ final solution” to the Jewish question by resettling 800,000 Jews outside Hungary. The “Arrow Cross” (Nyilas Parti”) party was the standard bearer of anti Jewish actions. By 1943 the governments anti Jewish rhetoric was toned down due Kallas’s secret talk with the Allies. However Jews were no longer involved in the public or cultural life of the country.

By March 1944 the Germans occupied Hungary because of the Hungarians secret talk with Allies, the country was going to be a battlefield due Russian advances to its borders and the Jewish population not having been deported to Auschwitz. By the above date as noted above 80,000 Hungarian Jews, mostly men were slain.

In April 1944 the orders to remove 437,000 Jews from the provincial town, cities and villages to ghettos starting on April ___, 1944 (that is now official Holocaust Memorial Day) and from there to assembly areas were issued in response to Adolph Eichmann’s order that was faithfully carried out by the Hungarian officials lead by the Hungarian police. Without the eager Hungarian cooperation this and the deportation almost exclusively to Auschwitz, starting in May, could not have happened. There were less than 100 Germans assigned to the task in Hungary. The Hungarians carried out all task in many cases with cruelty and handed the entrained Jews over to the Germans for destruction. There was essentially no protest against these actions by the Hungarian people. The Christian churches did save some Jews having Christian spouses.

The Hungarian Jewish leadership, led by a Zionist named Koestner, struck a deal with Eichmann to keep the fate of their coreligionist secret in exchange for permitting 1,658 Jews selected by Koestner, for $1,000 a head (money paid by rich Jew) to escape to Switzerland. Koestner ended up in Israel and given a government positions along with “protection”. After years the events descried, a Hungarian Jew, named Gruenwald and published a book documenting Koestner’s crimes. In response to this book the Israeli Government filed a lawsuit against Gruenwald for slander of Koestner (an unbelievable action by a government) and Koestner was found guilty. On appeal the Supreme Court, after several years took up the case and found Koestner not guilty. However, a second Hungarian Jew shot Koestner to death. The Israeli Government’s actions were amazing in protecting a Zionist functionary. Kostner’s criminal actions prevented Jewish resistance and other measures to avoid deportation. IN 1944, MY FATHER WAS GIVING GERMAN LANGUAGE LESSONS TO A HUNGARIAN ARMY WARRANT OFFICER WHO WANTED TO HIDE MY SISTER JUDITKA. NOT KNOWING OUR FATE MY PARENTS TURNED DOWN THE OPPORTUNITY. It is interesting to note that the Koestner “saved” 1,658 Hungarian Jews, included prominent orthodox rabbis with their families, who did everything to prevent the Zionist youth departing to Israel while the escape routes were still open. The generally strong anti-Zionist views of the Orthodox rabbis were well known, not just in Hungary, but also everywhere in Europe. The Zionist youth was to wait for Messiah to come before going to Israel. I have even witnessed fistfights in my community of Mezocsat, in the temple and temple yard, to prevent the Zionist “Agudas Yisroel” youth organization to have a Torah for their orthodox religious services.

All Hungarian Jews, except in the Budapest itself and a very few who managed to escape were deported to German concentration camps. In October 1944 the great majority of Jews in Budapest were housed in a central ghetto and the “remainder” moved into houses under the protection of the neutral countries of Sweden, Switzerland and Portugal. Death marches to Germany was ordered for Jews from the central ghetto and by January 1945, 98,000 lost their lives. By the end of WWII, 69,000 remained alive in the central ghetto, 25,000 in the protected houses and approximately 25,000 came out of hiding in Budapest. Counting all returnees from concentration camps and other places, out of 850,000, after WWII only 260,000 Jews were in Hungary with 565,000 having “perished”. Thousands of the 116,000 Jews liberated from German concentration camps did not return to Hungary, MY FATHER AND I AMONG THEM. About only 200,000 Jews survived the German concentration camps.

After WWII no laws were passed regarding the return of Jewish property. The anti-Jewish laws were repealed and those responsible (many have escaped justice by being in Germany and declaring themselves refugees) for the deportation and destruction of the Jewry were tried in courts of law. However, in 1946, pogroms occurred in Kunmadaras, Miskolc (MY BIRTH PLACE) and other communities. Diplomatic relations were established with Israel after its creation in 1948.

Under the communists, Jews were again persecuted. 20,000 were resettled from Budapest in 1951 and in 1953 they were permitted to return. In 1956 during the brief anti-communist revolution 20,000 Jews fled Hungary. MY AUNT REZSI, HER HUSBAND MENYUS, THEIR DAUGHTERS ANNI (ANIKO) AND MARTI LEFT, ENDING UP IN NY,). By 1967, due to continued emigration, the Hungarian Jews, including those not participating in the Jewish communal life, were down to 90,000. Presently, said population is estimated as 100,000. However, over 50% of said number is over 65 years old. Anti Jewish sentiment still exist in the country including physical attacks on Jewish “looking” persons. Assimilation is a major problem, yet this Eastern European Jewish community, relatively speaking, is doing well. THANKFULLY WE HAVE NO RELATIVES LIVING IN HUNGARY.

The Christian Churches through their political influence have persecuted the Jewish community. The Orthodox Jews, with a small exception, due to their dress, hair cut and head cover were immediately identifiable by anyone.

JEWISH COMMUNITY OF MEZOCSAT

The community was established about 1828 as strict Orthodox congregation. They built a temple that burned down and was replaced in 1880 with an impressive two story building that is now in semi ruin, because the lack of maintenance since 1944 by its owner the government of Mezocsat. Other institutions established were an elementary/middle school, winter temple (it was heated), “cheder”or “talmud tora”(religious school), yeshiva (advanced religious school), mikveh (ritual bath), slaughterhouse, chevra kadisha (burial society), housing for the rabbi and two cantors/shohets (slaughters) and a cemetery. Thus, it was an established community with a about a dozen non-religious families. Some time in the 1920’s my father became the principal/teacher of the Elementary/middle School. Prior to get married in 1930, and for a while after, he rented an apartment in on the main street in Mr. Barany’s house. During the time spaned by my memory, the rabbi was Fabian Altman whose son, “Scheeu”, was a classmate of mine. The head cantor was Mr. Cohen and the second Mr. Daskal (his son, Mayer, was my Hebrew teacher starting when I was 3 years old and my hair was cut short. Mayer used to pinch me whenever I did not know an answer). Mayer ended up in Cleveland, Ohio, and became the owner of several large nursing homes. Shraga Neumann, a wonderful individual, who also survived the holocaust and ended up in Israel, eventually replaced Mayer. Mr. Friedman and later his son-in-law Mr. Berkowitz taught religion in Hungarian language at my father’s school. Except for a Christian corporation owned company stores, established to compete with Jewish owned stores, named “Hangya” (ant,), practically all stores and enterprises were owned by Jews. Grocery and hardware stores were Glattstein (we shopped there almost exclusively), Friedmann, Saros, Breier, Beck, Droth and others. Cloth (not clothing) and shoes stores were Carl Roth, Friedlander, Saubermann and others. Sirmer and Heimfeld each owned a lumberyard Mr. Krausz (his son Sie was a friend of mine) made and sold wine. Mr. Mehrer sold and repaired radios. Mr. Ferencz sold and repaired large clocks (we stayed in one small room of his house, during our few weeks stay in the Mezocsat’s ghetto). Mr. Stiller was the shoes maker and shoe repairman. Several Jews made and delivered soda water. Lobel was one of two pharmacists in town (later the Christian license holder, Mr. Orosz, took back the business from him). Farm owners included Szekulsz, Resovszki, Borgida, Winkler and so forth. Attorneys were Dr. Furesz, Dr. Gocze and Dr. Bergmann (son Tibi was a friend of mine). Dentist, the only one in town, was Dr. Kardos, who was also a physician. The physicians were Dr. Kardos and Dr. Abonyi. Mr. Kolozs owned the only mill in town and both he as well his wife survived the holocaust. The veterinarian was Dr. Winkler. Mr. Engel owned the only bank in town (his son Laci married a Christian woman and, escaped deportation and his sister who became very sick in the concentration camp has survived.

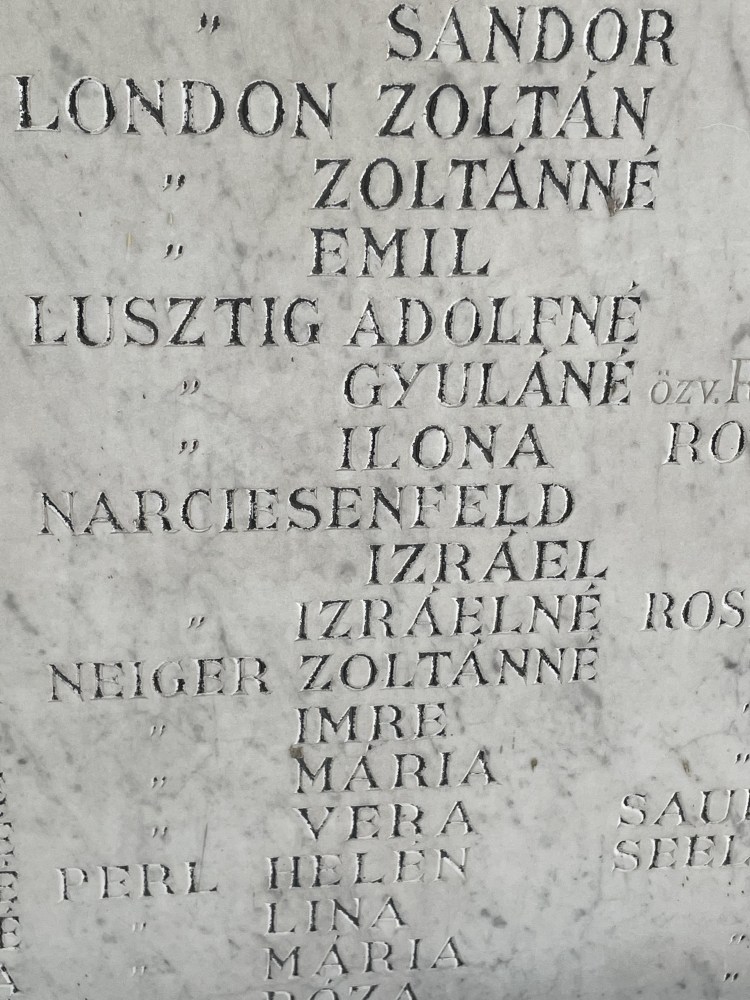

The WWII deportation of the community resulted in about 400 deaths by gassing and other inhuman ways (starvation, working to death, beating to death, shooting, exposure to cold, marching and frequently/children/old people burned alive at Auschwitz). Most of the very small number of people have survived concentration camps have only temporarily returned to Mezocsat. I know only four individuals who stayed there. The cemetery was not damaged and it is taken care of by a very nice couple living in the caretaker’s house next to the cemetery. There is a monument in the cemetery listing the names of the holocaust victims, including my mother, three brothers, and my little sister.

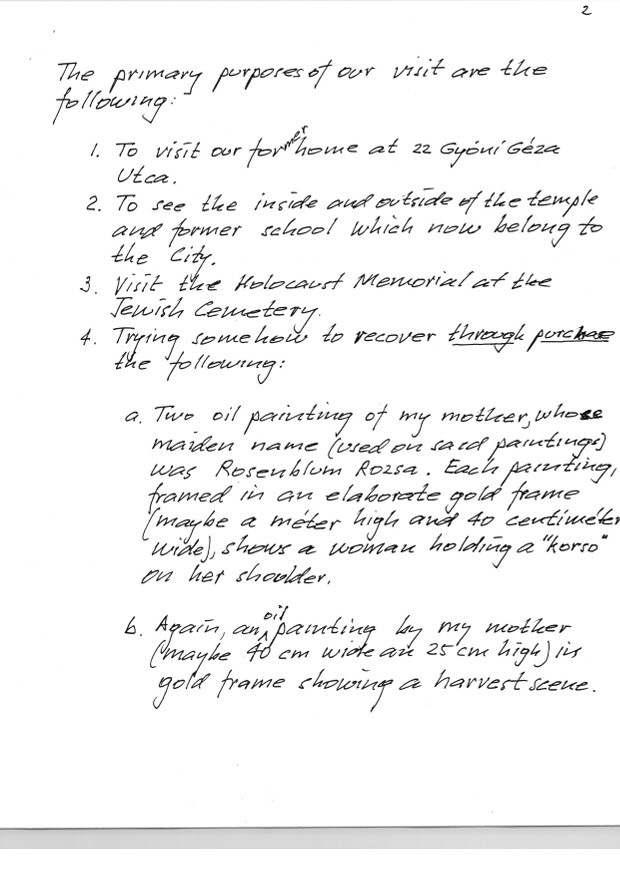

The Government of Mezocsat is undecided as to what to do with temple. At one time they tried to raise money from the expatriate Jews without success. They would use the building for multiple community purposes, including a museum. I have no use for Mezocsat or its citizens whatsoever. They have the contents of our house, including my mother’s paintings that I tried (advertised) to buy back without success. Now a main street and their high school is named after a Jewish poet Josef Kiss. Prior to WWII a marble slab dedicated in his memory was stolen repeatedly.

Anti Semitism has definitely existed and it was not helped by the facts that almost all Jewish kids had short cut hair and sidelocks (pajes), many grown-up Jews dressed differently, almost all retail and wholesale business was owned by Jews,

Due to Laws of Kosher Jews could not eat at Christen homes/places, except for business there was little almost no interface between Jews and Christians, the churches teaching of Jews being “Christ Killers” poisoned the relationship and the desire to rob the Jews of anything they could be an important factor. A very large number of Christian households have stolen Jewish property. They destroyed anything such as pictures and papers of personal nature. The most valuable books of father’s 2,000 plus books, library were probably stolen by influential individuals, and the rest was put in a library of some kind. After the German occupation Jews lost police protection. Me and my brother George were threatened on the street by a young man with a knife and my mother complained to a policeman living in our neighborhood, he told us that he could do nothing about it. Some Jews, kids, and adults were beaten up on the streets in the dark.

The fact is that the deportation of the Jews to Auschwitz simply destroyed the Jewish community of Mezocsat only our memory remains. As of about three years ago the son of a holocaust victim married to a Christian is the only Jew left in Mezocsat. No one stood up for us in the Christian community. With some exception, seeing or even thinking of Mezocsat and its people makes me sick. The only thing they did not do is to desecrate our cemetery, since there was no profit in it. One Jewish survivor, upon return to the town without his family, killed himself.

OUR FAMILY HISTORY UNTIL DEPORTATION

The very first thing I can remember is that I was in a part of our yard that was covered by grass and the son of the only blacksmith in Mezocsat, wearing a jacket with vertical red, blue and white colored stripes, lifted me on his back. My parents told me that I truly scared them, when I as a very small boy took my brother George out of his crib and carried him out to the tiled patio. I have no recollection of this at all. I was enrolled in the non-denominational Kinder Garden, but I did not adjust being away from home and as a result, my parents removed me from there. When I started school we mostly played with Jewish kids and sometimes with our Christian neighbors. Our most enjoyable playing was “hide and seek” in view of large yards and many auxiliary buildings. Summer we very much enjoyed our metal tub in the yard heated by the sun. We bathed naked and saw our guest Ann Hoffman, I have discovered that girls were not quite “finished” (since then my opinion has changed).

My father had a draft deferment, But a Lieutenant named Gestesi had arranged to draft and transfer to the Russian front “all” Jewish men of Mezocsat in such a rapid manner that everything, including serious health problems was ignored. He did the same to his Christian mistresses husband. After the war he was locked up for his deeds.

During the next few days after my father’s induction into the army, our mother has sent Gyuri and me over to Mr. Friedman’s for reading the psalm. While my father was in Russia the Hungarian Government stopped paying his salary obliging our Jewish community to pay it. They have refused to give us any money, except a small sum for not having provided us with a customary teacher’s dwelling. This was with the full knowledge of everyone including our rabbi and the elected leadership of our community. Thus, they left my mother and five of her children essentially without an income. The whole community forgot all the favors my father did for many of its members, having been the teacher of their children, common sense decency, and Jewish morality. Because of this, I have developed a hatred for said community as a whole, with a special hatred for specific above-noted individuals. All the while my father in Russia was helping everyone he could, including smuggling letters (through returning soldiers) to their families supplementing the postcard they were permitted to send. After the two companies have returned to Hungary and their members were discharged, each of them gave my father a beautiful thank you colored drawing with all members’ signatures. I can still visualize these two documents.

The above companies were attached to the German Army and my father became friendly with a number of their influential officers. When it became known that the Ukrainian Police captured three Jewish women and that they will shoot them, my father got two gold watches from his fellow Jews and bribed the Germans, resulting in freeing the women as being Christians. Thus, my father saved three Jewish lives in Russia.

Just before my father was discharged from the army my mother took Gyuri and me to her oldest sister’s, Aunt Blanca’s (Gruenwald family) home in Rohod for a vacation.

Eleven Months of Hell

by Lora Reed on October 30, 2021.

It is important for future generations to be aware of Tom’s life during World War II. The Holocaust isn’t just something to read about in history books. You are descended from a Holocaust survivor, who not only survived for eleven months in concentration camps but, guided by his father’s optimism and determination, managed to rise from the horrors of the camps, to become a man of great moral values, as well as a successful engineer and lawyer in America. His greatest goal was to establish a family. His greatest joy was to sit in his beautiful home surrounded by his glorious children and grandchildren.

In 1944, at the age of twelve, Tom and his family were deported from their home in Mezocsat , Hungary, with all the rest of the town’s Jewish population They were taken to the larger city of Miskolc where they, along with Jews from surrounding cities, were gathered into a brick factory yard. Men, women, and children lived together in this open yard without any privacy. After several days they were herded into cattle cars bound for Auschwitz-Birkenau. Upon arrival they were faced with German soldiers armed with rifles screaming “Mach shnell!” and large snarling dogs straining at their leashes. The prisoners were forced into two lines, women and children in one and men in another. Tom’s father made the fateful decision to instruct Tom to stay with him and when asked his age, to announce in a firm voice , “Seventeen”, in German, which was the family’s second language. No doubt his blond hair and blue eyes helped and he was passed on as a man capable of work.

Within an hour or so his three younger brothers, George, Oscar, and Frederick, and his baby sister, Judith, as well as his mother,Rose, and grandparents, were killed in the gas chambers.

You may have seen pictures of “life” in the camps. All belongings, including clothing and shoes, were taken and they were issued prison uniforms. They slept on wooden shelves several layers high, packed in like sardines. If one person turned over, everyone of that shelf turned over. They were fed with a ration of bread and watery soup and had to endure a lineup for count, regardless of rain or cold, that could last over an hour

Over the next months, Tom and his father managed to be sent together, to a series of work camps where Tom worked as a street cleaner, sanitation truck driver, or similar jobs, but still had to face each day not knowing if it would be his last. He saw prisoners shot, collapsing from starvation or work, beatings for trivial reasons, hangings, and suicides. Incidentally Tom told me that the intellectuals were the first to commit suicide while the orthodox held firm to their belief that God would save them.

Tom almost died from a bout of cholera, but a Jewish doctor managed to save him even though he had no medicine with which to treat him.

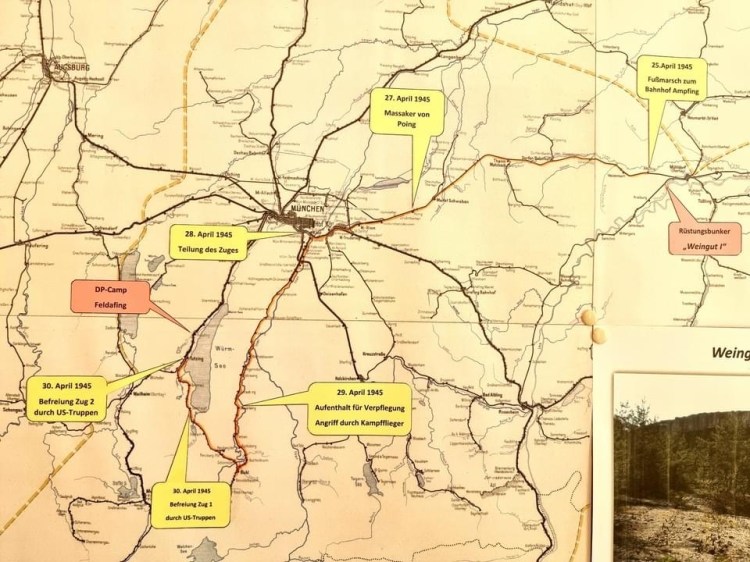

As the war was drawing to a close, once again they were herded into cattle cars. His father made a deal with a guard – they agreed to try to protect each other during the dangerous hours to come. When the train stopped they heard shouts that the war was over and they were free! Tom’s father was suspicious and insisted they should stay in the boxcar for awhile.

Sure enough, as the Jews leaped off the train, German soldiers came out of the nearby woods and shot the escaping prisoners. Tom told me about watching a man, shot in his head, trying to eat his last bit of bread before dying. A German soldier jumped into the car and raised his rifle to shoot Tom, but the guard argued him out of it and saved Tom’s life. To add to the chaos, as the ground shooting stopped, allied planes appeared overhead, and mistaking the train for a troop train, began straffing both the prisoners and soldiers alike. Tom was shot in his upper thigh.

When the American troops arrived they ordered German soldiers to carry Tom’s stretcher to the hospital. Tom refused to be taken by the Germans until American soldiers accompanied the stretcher. The bullet remained in his leg for the rest of his life.

How he managed to survive all those months of Hell is indeed a miracle, possible only because his father was there to bolster his spirits and encourage him to keep going day by day. But I cannot help but feel an even bigger miracle was that Tom could grow into a strong, good , and kind man. It was only after his retirement , perhaps because he was frequently asked to speak before groups, that he began dwelling on that period of his life. He never wanted to hear any bad news, quickly changing the conversation. Only once did I see him cry. While on a cruise, we attended a Jewish religious service. As we approached the room, we could see the people praying while swaying back and forth, as is the custom for Orthodox Jews. He began to cry and said “It’s just like home”.

Written by Lora Reed

This story was actually written for “The Jewish Georgian” by both Tom and I after our trip to Germany.

It has been fifty-seven years since I, as a twelve year old child was deported with my family from Hungary to Auschwitz, and then to Germany. Now the time had come for me to revisit those concentration sites in Bavaria where I had been imprisoned during 1944-1945, as well as my hometown of Mezocsat. My wife, son, daughter-in-law, and grandson accompanied me on this trip to my past. By coincidence, my son and grandson were the same ages my father and I had been when my saga began.

Except for three weeks in Auschwitz, where my mother, three younger brothers, baby sister, and paternal grandparents were murdered within a few hours of our arrival, my internment had been in Muhldorf, Mettenheim, and Mittergars. These camps are generally relegated to the very back pages of Holocaust history, but to those of us who were there, they remain a very significant part of our past. The suffering, brutality, and death at those camps are an everlasting part of our souls.

In preparation for the trip, I sent a letter to the mayor telling him of my arrival date and asking his help in locating any of my mother’s paintings, which I hoped to purchase from the present owners. A response was not forthcoming. I had better luck with my preparations for Germany when I found a representative of a group in Muhldorf interested in the history of the camps. Arrangements were made to meet at the Ampling train station. And so my trip began.

Meszocsat lies about two hours north of Budapest. I recognized it immediately as we drew near the Protestant and Catholic Church towers that loomed ahead. My initial impression was surprise at how much smaller everything seemed. The streets that seemed so wide when I walked on them all those those years ago were in reality, barely two lanes, the buildings that had seemed so grand to my young eyes were small structures that would have been declared shabby in an American town. The side streets were still unpaved, just dirt roads unchanged in half a century, and our shoes and car were soon covered in dust.

A few things had changed. Old, dirty cars had largely replaced the horse drawn carts, and most of the thatched roofs had been replaced by tile. Where once had been well-tended gardens now stood typical small stucco homes. Thatched roofs are still plentiful in the countryside, as well as the familiar storks nesting atop tall poles. The total population of Mezocsat remains stable at about 6,000, but the make-up of the population has changed. Where 407 Jewish citizens lived, now only one (born after WWII) exists.

Lora Reed, October 31, 2021

Chapter Two

We went first to the temple and adjoining Jewish school where my father had been a teacher and director. It wa a heart breaking sight that affected each of us. The buildings, which had been used as warehouses after our deportation, were a total shambles. The outer walls of stucco had disintegrated and the underlying brick was falling apart. Windows had been broken and boarded up. The doors, which hadn’t been sealed during the warehouse years, looked like entrances to a medieval ruin. Inside, the floor of the women’s balcony was unsafe to step on and, except for a few pillars, all that remained was the shell of the building. In my mind I could hear so clearly the prayers chanted within those walls by my family, friends, and neighbors. I wondered, as I had so many times, how God had allowed this to happen.

We went to the Jewish cemetery which was surrounded by a chain link fence topped by barbed wire. It is well- maintained and undisturbed. The large headstones are in good condition. Next to the narrow dirt path leading to the cemetery is a ditch filled with stagnant, putrid green water, and adjoining that is now the town dump, A memorial to the towns Jews, paid for by the survivors, has been erected with the names of those killed engraved in the stone. We traced the names of my family, said our prayers, and left our stones. The wife of the caretaker stood by , patiently waiting with a bucket of water and clean towels for our use.

From there we drove to the railroad station. I walked on the very same steps my family had climbed to be loaded into the cattle cars destined for a brick factory in Diosgyor, and ultimately to Auschwitz. There, with but a few exceptions, we were all- rich or poor, wise or simple- to become fodder for the furnaces. I remember my father asking the csender, as the Hungarian rural police were called, to be careful as he loaded my mother onto the cattle car because she was pregnant.

We didn’t know how we would be received in the mayor’s office, but were courteously received by the mayor’s secretary. After ushering us into a large conference room, she served us coffee, cold drinks, and cookies. My Hungarian served us quite well, and after perhaps fifteen minutes of conversation, the secretary revealed that she was my former neighbor ‘s daughter. I was so stunned that I took my head in my hands and, so my wife tells me, said,”Oh my God, my God,” in English. I remember fondly my neighbor and her house. My brothers and I had played in her yard as readily as our own, and the families had had a warm relationship. My father had made an arrangement with her parents. In exchange for some of our tools, they would bring milk for the children at the brick yard, but they never fulfilled their part of the bargain.

Chapter Three

We exchanged family pictures, and then she took out two letters my father had written to her mother-in-law from Feldafing, the DP camp where we lived after liberation. The letters told the family that only he and I had survived and asked about the condition of our home. Neither letter received a reply, but now my neighbor told me how our home was robbed by well connected people after we were sent to the ghetto. It had taken a whole wagon to carry off my father’s much-beloved library of over 2,000 books. Perhaps it is the memory of those books that made me such a fanatical book collector. As to my mother’s paintings, there wasn’t a trace, even though the mayor had advertised for them in the Mezocsat bi-weekly.

My home no longer existed which was perhaps just as well. It would have been difficult to think of others enjoying our home after our tragedy. In its place stood a shabby new house. The owner unchained and unlocked the gate to allow us to wander around the yard. The vegetable garden was neglected, the flower garden no longer existed, and everything looked small and sad.

When I was a child in that town, as a special treat I would walk with my father to a then Jewish-owned neighborhood tavern where I was allowed a few sips from his beer. Sure enough, the tavern still stood and we finished the day with my son, grandson and I sitting around the table and sipping from a beer. As my wife said, it had been a long road from Mezocsat to Milton, Ga.

One final adventure adventure awaited us in Hungary. Several

years ago, the Hungarian government offered reparation money. However, the recipients were required to collect the money in person in Budapest. We took a cab to the claims office, located in a shabby part of town, behind another barbed wire fence with the additional protection of a watchdog and a sign warning of an armed guard. Undetered, we entered and opened the door to the unmarked office and found what could have been a scene from a Grade B movie. The stark room had no receptionist, only a few wooden chairs lined the left and right sides, and facing us were bare white cubicle walls. At first we thought no-one was there, but found a young lady in the last cubicle who took my information and asked me to come back in half an hour. Upon our return she gave me documents approving payment of 170,000 forints. However they did not keep the money there. We had to go to a particular bank located only a few streetcar stops away. The bank wasn’t hard to find, but there we were told that, yes, this was the bank, but the wrong branch, which, we were told, had no bank sign, but could be recognized by the large black doors. After knocking on the wrong doors a few times we found the mysterious bank, which looked quite proper and substantial inside. The teller assured us she would have the money in just a few minutes. She returned with 170,000 forints all right, but in government bonds. “What can I do with these?” My only viable option was to cash them for the going rate of 30% of face value, and she happened to have a contact willing to do just that. Within twenty minutes a young man hurried in to the bank, opened his briefcase, and we quickly traded. He left with my 170,000 forints worth of government bonds and I with $170.00. Well, that paid for my cab and dinner at Gundels with my family.

Lora Reed, November 09, 2021

Chapter Four

Only my wife and I continued on to Germany, where we met with Mr. Egger, who had taken a day of vacation to be with us. He was invaluable, as none of the places of my internment is on a map, not did a single one have any kind of identifying sign to mark its location. He drove us on a narrow dirt track deep into a forest to what had been the Muhldorf-Wadlager (forest camp). Due to its location and the fact that people had lived in underground hole-like structures, the camp features were quite traceable. I was at this camp on only one occasion, carrying some object from Muhlldorf-Mettenheim where I was held prisoner. The forest camp held about 2,250 men and 500 women, almost all Hungarian Jews. The primary purpose of the camp was to supply labor for building a Messerschmitt bombproof aircraft factory for the production of the Me 262 dual engine jet fighter. From there we drove into another forest through narrow trails and suddenly emerged into an open area. There ahead of us loomed the only remnants of that awful place. All that remained of the facility, which had once covered an area of about five football fields, was a small portion of a hangar. The facility was destroyed by the German government under US orders and supervision, and it took two blasts to accomplish. The Jewish prisoners had worked there in two shifts, six days a week, twelve hours a day, each carrying a 110 lb. cement sack on his back, forming a continuous human chain up a ramp 45 feet to the cement mixer. Others dug the utility tunnels and did other hard labor. About 2000 Jews worked each shift with almost no food, wooden soled shoes, and no warm clothing. Over 400 physicians sent from Auschwitz were assigned to carry cement, and they all perished. People were routinely beaten to death by the supervising non-Jewish prisoners or the German masters. Ironically, the factory was never finished. Of the approximately 10,000 Jewish prisoners who were sent to the camps in the Muhldorf area to maintain a headcount of about 4,500, over 57% perished. Of those who died, approximately 50% died in 2 1/2 months, within five months, 90% were dead. Most are buried in mass graves. All that marks the spot is one span of the arch, dark and foreboding, over a barren landscape, with bits of cement falling and metal screening showing through. I brought home some of those pieces of cement to remember the suffering and death that went into each piece. That was the only site we visited that retained a feeling of evil . The eerie quiet was menacing and ghostly; I think even the most innocent of its past would have felt uneasy in that place.

Chapter Five

The visit to Muhldorf-Mettenheim and Mittergas, where I had spent 9 1/2 months of my imprisonment, was disappointing. The Muhldorf camp and adjacent Luftwaffe base had simply vanished. A peaceful housing area stands where the camp had been, and a wheat field has replaced the airbase.

As a street cleaner in that camp, I dumped trash into a large, deep pit, and now I stood at the edge of that transformed hole. It had been partially filled in, and is now a beautiful sport facility. Rows of seats filled the walls of the former pit, and where I had dumped trash, children now played soccer. Nothing marred the perfectly charming suburban scene. Yet the residents must have been aware of its history. Their children play on ground soaked in our blood.

Interestingly, the camp commander, Sigmond Eberle, an American Nazi, who went back to Germany to serve Hitler, was freed by the U.S. Dachau War Tribunal, and lived out his life near Dachau. Yet the key individuals under him, as well as his direct superiors, were hanged. He was cruel and in my opinion, directly responsible for most of the deaths at the camp. I am trying through my German contacts, to unravel the mystery of his acquittal.

Mittergars is now a field of wheat. In the adjoining forest, where the guards had lived, we found the foundations of two SS Baracks as well as the concrete punishment cell. As I was walking around the site, an old man on a bicycle came pedaling up the dirt track. He stopped, and obviously curious about our presence, said hello. I began chatting with him and found that, although he had been based elsewhere during the war, his friend had been a guard at the camp. Not only that, but he had copies of his friend’s documents relating to the camp. He invited us to his home where we were seated in the backyard and his wife treated us with refreshing cold drinks. He brought out a folder of papers, and as I thumbed through them, I was shocked to see a familiar handwriting. There, before my eyes, was a post WWII affidavit, written and signed by my father, stating that this guard, Helmut Schwalm, had been humane in his treatment of the prisoners. How incredible that here I’d be, 57 years later, sitting in a Bavarian peasant’s backyard, and by pure chance stumble upon this document

I was thankful to return to Georgia. I felt I had to see those places in Poland and Germany once more, but I found no peace for myself in Europe.

“There can of course be no question that the primary responsibility for the massacres of the Jewish population in Hungary rests with the Germans. But it seems that the Final Solution of the Jewish question in Hungary was only a wish and not an absolute demand of the Germans. Moreover, the Sonderkommando that was at the disposal of Eichmann, consisted only of a small contingent two hundred men, who on their own, could have done little without the active help of the various Hungarian armed formations that were put at his disposal. The actions of Bulgaria, Finland and Romania, and the July 1944 action of Regent Horthy himself putting an end to the deportations show that had they wished to do so, the Regent and his men could have saved most of the Hungarian Jews. However, Horthy’s clique was interested only in saving the members of the Jewish financial elite with whom they had advantageous relations and welcomed the opportunity to rid the country of the “Galacian” Jews and the Ostjuden. That is today that the rulers of Hungary were as much responsible for the Jewish genocide as were Eichmann and his SS.

Added to this was the active dislike of the Jews that characterized large segments of the Hungrian peole and enabled the Hungarian commanders to rely on many in the ranks of the gendarmerie, the police and the army to carry out the deportation and mass murder if the Jews with unrestrained brutality, while the public at large stood by with indifference and helped the Jews only in a few exceptional cases.

While the Germans and the Hungarians thus bear the main responsibility for actively orchestrating and carrying out the Holocaust, secondary, passive responsibility must be assigned to the Allies and the Catholic Church. Their interest in saving the Hungarian Jews, was to say the least, lukewarm. To mention only one instance, the Allies were asked to bomb Auschwitz and the rail lines leading to it and thus make it impossible for the Germans to proceed with their organized transportation of Jews to death factories. The Allied response was they they could not spare planes for bombing “secondary targets”, but they were able to send large numbers of bombers to destroy Dresden, a target of no military value at all.

And finally, and most painfully, some responsibility must be assigned to the leadership of the Hungarian Jews and especially those in the Capital, Budapest, remained convinced to the very last minute that “it can’t happen here.” The traditional ingrained patriotism blinded them to the inexorable progression in Hungary of deadly anti-Semitism a la Nazi Germany, and by serving in the Jewish Council and obeying instructions issued by German and Hungarian authorities, they become willy nilly cogs in the Nazi-Arrow Cross killing machine. Even if we assume that they all acted with the best of intentions and were totally committed to doing what they believed was best for the community they represented, what is tragically patent is that their function contributed to the orderly procedure of first depriving the Jews of more and more of their rights, and in the end, sending them to their death without any appreciable resistance. Th is, within the general tragedy if Hungarian Jewry, was the special tragedy of its leadership in the days of the war and the Holocaust.” Raphael Patai, author of The Jews of Hungary

Another Perspective-

When our son Alex Jacob Reed was 12 years old, Barb and I took him to Europe, stopping in Prague before meeting my parents in Hungary. We stayed in an amazing apartment on the Buda side of the Danube River while my parents stayed in a beautiful modern Marriott on the Pest side of the Danube. We spent about a week in Hungary, first exploring Budapest and then ultimately, the real reason for the trip, a visit to Mezocsat, my place of my father’s childhood. While in Budapest we ate at the world famous Gundel’s restaurant, compliments of the so called reparations Hungary paid my father for the loss of his family, home and personal property. We explored Jewish Budapest, visiting the great Dohoney Street Synagogue where my father, joker that he was, promptly got in trouble for climbing a ladder in the middle of the sanctuary. The temple also had a small museum we visited, Outside of the temple was a memorial to the murdered Jews paid for by the American actor, Tony Curtiss for his Hungarian born father, Emanuel Schwartz.

We roamed in the streets and parks in search of my father’s favorite foods-many sweets, water “mit gas” (bubbles) and of course, cholent, a heavy, heavy bean dish that my father always loved (and received from my mother for special occasions although hers did not exactly meet the strict kosher standards that my father was raised with as my mother’s recipe contained pork!). We visited bakeries, farmers markets, government buildings, rode the funicular, bathed in the hot pools and luxuriated in steam rooms, shopped at local markets, rode the trains and ate in the locals places. My father enjoyed speaking the Hungarian language again and he and my mother both enjoyed the City.